WHERE OUR RADIOACTIVE WASTE WINDS UP

FROM APRIL/MAY 2021 ISSUE OF WEST END PHOENIX

The small uranium pellets produced at 1025 Lansdowne Ave. are fuelling a fight in South Bruce County, one of two communities being considered as sites for burying nuclear waste underground

The community of Teeswater in South Bruce County, Ont., has a year-round population of less than 1,000 people and 50-50 odds that it will be the permanent home to thousands of tonnes of Ontario’s spent nuclear fuel.

Michelle Stein, chair of the Protect Our Waterways board, has been leading a vocal group of residents concerned over what a $23-billion proposal to bury used nuclear fuel 500 metres deep in a 1,500-acre subterranean space called a Deep Geologic Repository (DGR) could mean for their farming community. The focus of Protect Our Waterways’ frustration to date has been the Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO), a not-for-profit founded in 2002 to design and execute the long-term management of Canada’s used nuclear fuel.

Shortly after learning last year that the DGR could be sited in their community, Stein and her husband spoke with NWMO staff at their office. “Our main question for them was: If this project affects the quality or the quantity of our water, what will you do? What will happen?” Stein said over the phone in late March, from her home in Teeswater. “Bottled water doesn’t work on a farm. We raise sheep and beef cattle and cases of bottled water aren’t going to work.”

Stein’s concern stems from the potential for water to erode, rust through or otherwise seep into the DGR and, once exposed to the radioactive material, leak back out, carrying its toxins into the groundwater or tributary rivers of nearby Lake Huron. Stein didn’t believe she and her husband received a satisfactory answer to her question about what will happen should her groundwater become polluted; it sparked what’s become something of a second job, leading her to conduct presentations at community meetings and speak frequently on the subject with media. “That day we walked out of the [NWMO] office and decided that we needed to start looking for some real information,” she says, “because either the NWMO didn’t have answers or they were scared to tell us the truth.”

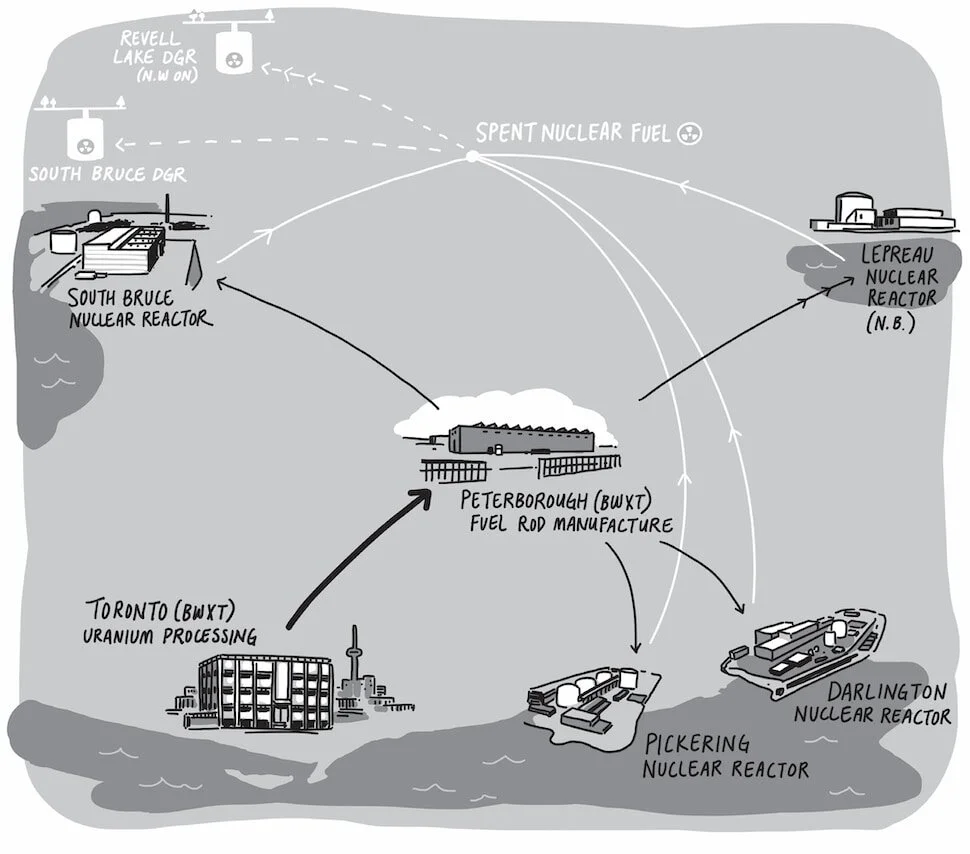

While the debate swirling around the storage of nuclear material centres on counties some 200 kilometres west of Toronto, the cycle of nuclear power production in the province begins in some respects at 1025 Lansdowne Ave., just north of Dupont Street. There, in a squat, beige, four-storey building, the Canadian affiliate of the Lynchburg, Virginia-based company BWXT presses, bakes and grinds uranium powder into ceramic pellets. From there the pellets are shipped to a BWXT Canada facility in Peterborough, Ont., where they are bundled for use in CANDU reactors. The company boasts that the pellets produced in the Wallace Emerson neighbourhood are responsible for generating a quarter of Ontario’s electricity.

The discussion about what to do with spent nuclear fuel is a longstanding and, unsurprisingly, acrimonious one. Ontario generates 58 per cent of its electricity from nuclear power and, as of 2018, has some 57,000 tonnes of spent nuclear fuel being stored above ground on-site at existing nuclear facilities with nowhere to store it long-term. In 2007, Canada’s federal government signalled that the DGR approach was its preferred option for long-term storage. Three years later, NWMO began the search for a community willing to host the DGR. And while 22 communities indicated their interest in learning more about hosting the facility, just two remain – Ignace, northwest of Thunder Bay, and the Teeswater location.

For Stein and Bill Noll, a fellow Teeswater resident and spokesperson for Protect Our Waterways, the concern extends beyond potential pollution of local bodies of water. Stein cites the daily haulage of radioactive material through the community to the proposed site as a major worry; for Noll, it’s the fact that, once sealed, there’s no going back.

“Ontario generates 58 per cent of its electricity from nuclear power; 57,000 tonnes of spent nuclear fuel is currently being stored above ground”

“There’s no ability to retrieve anything from the cavity. The design is not created that way – it’s created to be stored and left there indefinitely,” he tells WEP. If groundwater sources are polluted by the DGR through leakage, “future generations are going to say, ‘What’s this all about? How did our water get so polluted?’ They may not even know there’s nuclear waste down deep in the ground, because it’s going to look like there’s nothing there.”

Yet the fears over leakage often reflect a misunderstanding about the nature of spent nuclear material emerging from CANDU reactors, NWMO spokesperson Salima Virani tells WEP. “Canadian used nuclear fuel is not a liquid or gas that can leak – it is a stable solid material that will be sealed and stored in a deep geological repository” that relies on a “system made up of natural and engineered barriers made of low-permeability bentonite clay and robust containers.” Deep geologic repositories in Germany and the United States that are often cited as examples of the failure of DGRs to store nuclear material are inappropriate comparators, she adds. The German Asse II facility between Hanover and Berlin was originally a salt mine converted in the 1960s to store nuclear materials, while the U.S. facility in New Mexico stores transuranic radioactive waste, typically protective clothing or tools used in the recycling of nuclear fuel or the production of nuclear weapons.

Canada’s used nuclear fuel is currently stored above ground in licensed facilities at reactor sites, Virani says. “This method is safe, but temporary. It is internationally recognized that this method is not appropriate for very long time frames. Used nuclear fuel must be contained and isolated, essentially indefinitely.” The DGR concept is based on the culmination of 30 years of research and agreement from scientists around the world that has found it to be the safest method for isolating and containing radioactivity from used nuclear fuel. Sweden, Finland, South Korea and Hungary currently use deep geologic repositories to store their nuclear material.

Meanwhile, roughly 300 kilometres east of Teeswater, in Peterborough, legal action was taken in February 2021 by the Canadian Environmental Law Association (CELA) challenging a recent licensing decision by the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission. In December 2020, the CNSC granted uranium pellet manufacturer BWXT a 10 year operating licence extension: In doing so, CNSC gave BWXT the right to shift pellet production from its Lansdowne Avenue location to its Peterborough facility if it so chooses, though it could not manufacture pellets at both sites. This, CELA will argue, shows a failure on the part of Canada’s nuclear regulator to investigate potential environmental, health, and safety concerns of switching from merely packaging uranium pellets to actually manufacturing the pellets, a violation of Section 24(4) of the Nuclear Safety and Control Act.

“The CNSC must be satisfied that the licensee in carrying on that activity, whatever the activity may be, will make adequate protection for the environment and human health,” CELA counsel Kerrie Blaise tells WEP. “And we’re saying, ‘Well, [the CNSC] can’t come to that determination if they didn’t have the necessary information before them to even determine if adequate protection will be made.” CELA agreed to take on the case after Citizens Against Radioactive Neighbourhoods began raising concerns with BWXT’s operating licence extension, given its facility is located 25 metres from Prince of Wales elementary school. (BWXT declined to comment for this story.)

Field work is currently ongoing at both the South Bruce and Ignace locations. NWMO has recently secured access rights to 1,500 acres of land near Stein’s farm to conduct preliminary testing, including borehole drilling. For Stein, the DGR is a problem no matter where it’s sited. “The waste is still going to be sitting on the lakeshore,” whether it’s stored in aboveground facilities near nuclear plants on Lake Ontario, below ground at a DGR beside Lake Huron, or at Revell Lake near Ignace. “Basically all a DGR does is move some of the material to a new location and cause risk in a new area.”

The unknowns loom large for Stein. “Everything about this is an experiment.”