Punching Tomorrow

FROM APRIL/MAY 2023 ISSUE OF WEST END PHOENIX

The 13th Round boxing gym on Primrose Ave., just north of Dupont and Lansdowne, provides free 13-week programs that offer young participants sessions with boxing coaches, healthy snacks, space to hang out with one another and access to a social worker.

At a boxing gym in the Junction Triangle, a free program is teaching young people from underserved communities how to cope with the challenges life throws at them

Bri stands with her left foot in front of her right, legs slightly bent. Her boxing gloves are raised to her eyes, which are locked on the two soft pads held by her coach.

After a few seconds of calm, she strikes. The coach raises his left pad, and her right glove sharply moves through the air and hits the pad. Pow. He raises his right, and she punches the second pad with her left glove. Pow. She does this over and over in quick succession, her stare never wavering from the targets.

She’s fast and focused. After a year of coming to the 13th Round Fight for Life boxing gym, on Primrose Avenue in the Junction Triangle, 13-year-old Bri has memorized those technical moves.

A half-hour after the class is over, she’s changed and relaxed in a sweatsuit. Now Bri has her glasses on, her long braids down by her face. She carries an inhaler, just in case. Her asthma has been crippling in the past, but no one watching her box would guess that.

“I am really comfortable at the pace I do,” she says. “I try to do my hardest.” Her mother encouraged her to join the gym’s co-ed youth program, which offers 13 weeks of one-hour sessions with coaches and skill-building for free. “I’m glad I did, because if I didn’t, my mental health would be worse than it is now,” Bri continues. “It was really, really bad before I came into boxing. I was such a mean person to myself.” Bri, who is Black, describes past friendships with schoolmates in which she was bullied and body-shamed. As a preteen, she reacted by punching lockers or by swearing. “I was so mad to the point where I had a mental breakdown at school.” But her involvement in several sports, including her school’s volleyball team – and, especially, boxing – gave her the chance to learn not only to self-regulate, but also to continue building confidence and make new friends, who cheer her on in the ring.

“I got better mentally and physically, so that helps me a lot,” she says.

For young people such as Bri, who lost crucial years of development around community, fitness and social connection due to the pandemic, becoming involved in the gym has been more than a way to build stamina and keep active – it’s been an anchor for their mental wellness.

The gym, which opened a year ago, offers teens like Bri – along with adults – opportunities to work on their fitness, build a community and get mentorship and emotional support. The studio’s staff say the goal is to set people up for success, develop invaluable life skills and boost their mental wellness to cope with whatever life throws at them. These teens who have gone through the pandemic know all too well how fast life can spiral out of control.

For youth from underserved communities that deal with multiple systemic barriers, including neighbourhood neglect and institutionalized racism, programming that is easy to access is crucial. And that goes beyond cost.

A young person might not have access to reliable transportation and need a gym closer by, or maybe extra travel cuts down time to grab a snack before class. That’s where 13th Round comes in, says Kerry Emmonds, its executive director.

“We’re not diminishing the systemic barriers writ large, but we are trying to pull the pin out of them on the ground level by being within an hour of the demographic we’re trying to support. It’s a low-barrier approach of offering access.”

At 13th Round, one of the boxing coaches is a social worker who is available to talk in a private room if participants need help. There’s also an upstairs area where teens can hang out with friends they’ve met through the program (it was originally meant for homework, but that doesn’t always happen).

A spread of snacks is provided each session. The selection varies but is meant to be reminiscent of a home-cooked meal. There’s also a large outdoor patio for summer gatherings.

The need for services and studios that provide accessible fitness classes for the community and also aim to foster social development and build the confidence of youth is more urgent than ever, as the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Toronto’s youth continue to reverberate, community workers and academics told the West End Phoenix. Physical activity that isn’t centred around appearance or weight is important not only for growing self-esteem, says Dr. Amy Gajaria, a clinical scientist and psychiatrist specializing in underserved youth and families, but is also crucial “for young people who may not have other outlets for managing difficult emotions or life events.”

The city of Toronto’s budget for 2023, announced in early February, saw increases for services like police but not for community organizations, more than 200 of which received close to $26 million last year. The same was allocated in 2023, with no increase to address inflation.

According to the Ontario Nonprofit Network, which represents the 58,000 organizations in the province, the 2023–24 Ontario budget represents a “piecemeal approach” that will stabilize some community services but is not enough funding to offset rising costs due to inflation. Though elements of the budget include $3 million for the Black Youth Action Plan, a province-led initiative that aims to reduce systemic, race-based disparities, as well as a five per cent increase in base funding for the mental health and addictions sector, the network states on its website that multiple portfolios including Children, Community and Social Services received only a five per cent budget increase, which it calls “meagre.”

Patchwork funding, or one-time pilot funding, means great programming often comes and goes in communities. “These organizations,” notes Gajaria, “need enough funding to have longevity.”

Though 13th Round is a registered charity and was kick-started by investor Bruce Croxon of Dragons’ Den, such organizations are continually looking for partners to support their initiatives, Emmonds says.

And the need for these options is only heightened specifically for youth from underserved neighbourhoods who were disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and are often from immigrant families coping with pandemic fallout and skyrocketing inflation.

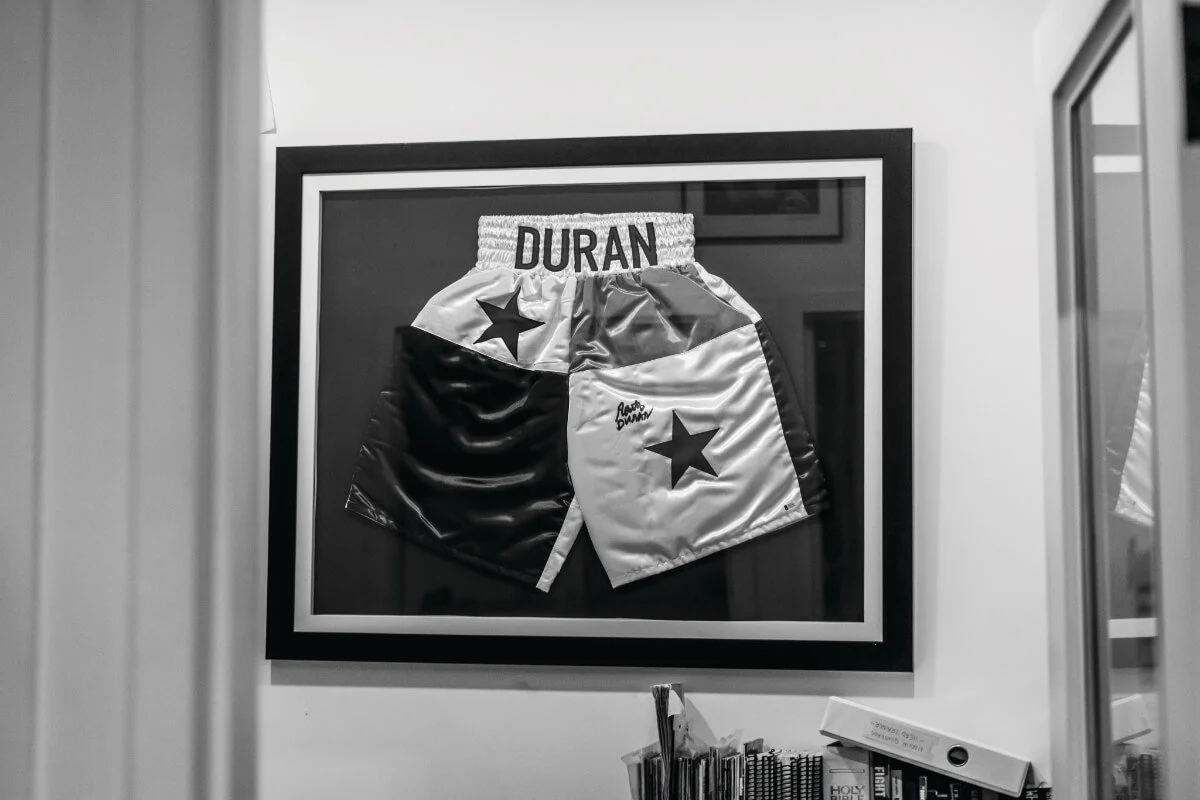

At 13th Round, the walls are painted a bright white, and there are dynamic framed prints hung on the walls. The women’s bathroom has a print of a female boxer and drawings of women dressed in 19th-century clothing – long dresses – but looking tough and wearing boxing gloves. Spend a few minutes in there and you picture yourself in the ring.

It’s close to 6 p.m. on a Wednesday night, and the teens are halfway through their class. They are striking punching bags and boxing with a partner. They take a few minutes to run laps around a nearby boxing ring while their head coach, Marvin Quinteros, shouts words of encouragement.

“A Cambridge University Press study found that neighbourhoods with greater community support buffered stressful life events for kids, leading to fewer incidents of aggression and depression”

Quinteros was a provincial boxing champion in the 1980s and, after his career wrapped up, he worked with marginalized youth for many years. “It’s the philosophy of boxing – it’s not just about the discipline, it’s about the community atmosphere,” he says. As he speaks, there’s a burst of laughter and chatting from the youth as they run around the ring (“Be careful guys, don’t wreck anything!” Quinteros calls out).

This is 13th Round’s third cohort of kids to go through the program, with some who are back for their second or third session. “At first, they’re all wide-eyed, and they really don’t know what they’re getting themselves into,” Quinteros observes. “As the weeks progress, you see them having both a mental and physical push. They end up really enjoying it.”

They learn, he continues, that “it is good to push yourself, both mentally and physically...to stay until the end of class.”

For an hour after their workout, students can either continue boxing with volunteers or spend time upstairs, enjoying snacks, talking to the social worker or playing games with friends. Though there’s no pressure to stay, one recent day there are about 10 of them upstairs, snacking on pita, hummus and carrots. Some play cards and, based on the volume, it seems to be a particularly dramatic game.

Quinteros points to a group of boys. “They all have their cliques now,” he says. “They’re really folding into the mentality of being a community and helping each other out.”

I speak with Bri and fellow boxer Chanté Elliott, 19, in a separate room as the card game proceeds. Chanté is soft-spoken and pensive. But she laughs with Bri when they talk about their first meeting. Chanté was impressed by her young friend’s boxing skills. “She has asthma, but when she’s at the bag – it’s like, wow.”

Chanté goes on to explain how her promising career in basketball was derailed when COVID-19 hit. “I was a full-time basketball player, from Grade 7 until right before the pandemic started. I was travelling all around Ontario.”

Now, Chanté – who worked part-time in the service industry to pay for basketball fees – is focusing all her energy on boxing at 13th Round. And she’s happier for it, she says, as she can focus on her own skills rather than worrying about the cohesiveness of a team. What’s more, 13th Round has brightened her spirits, which darkened when she moved from high school at George Harvey Collegiate to college; she started in 2021 but is taking a break this year, and returning to classes in the fall. “My mental health is one of the reasons why I came here,” she says. “My mental health was deteriorating.”

“I’m not depressed anymore,” Chanté continues. “I rarely have anxiety [or] other things that bother me; I’m able to let go of things.”

Clearly, programs like 13th Round are about more than just fitness, though it’s well-understood that physical activity bolsters mental wellness, says Mark Ferro, the Canada Research Chair in Youth Mental Health and an associate professor at the University of Waterloo. Community fitness programming that is multi-pronged and creates a social network and space to connect with resources such as a social worker ends up “fostering cohesion within the community across generations, young people and adults.” He adds that the pandemic was a “major blip” requiring programs for children and youth beyond schools.

Ferro points to research published by Cambridge University Press indicating that in Canada, neighbourhood social cohesion can have a protective effect on youth mental health after traumatic life events. The study, published in 2019, found that neighbourhoods with greater community support and connection buffered stressful life events for kids, leading to fewer incidents of suicidal ideation, aggression and depression.

And in Toronto, the need to support neighbourhoods that have faced decades of neglect by multiple levels of government, through decreased funding and resource allocation, has become more pronounced due to the pandemic. Communities with more low-income families, often racialized and from immigrant backgrounds, have been more susceptible to the virus.

It’s also youth from those families who are most in need of programs like the one offered by 13th Round, says Gajaria. “A lot of us remember our high school years. It’s a foundational part of a young person’s life. It sets them up for a lot of things. Frequently, children who have worsening mental health during those crucial years and struggle with success will have those problems reverberate throughout their lives.”

Gajaria says while there is limited research on Toronto neighbourhoods specifically, she cites recent studies that indicate accessing mental-health services is disproportionately challenging for Black youth in Canada. A 2020 literature review from academics at McMaster University and the University of Toronto found that Black children and youth were more likely to face increased wait times, financial barriers and services not being close by. Racism and discrimination from providers was also found to be an issue.

Through her own work and research, Gajaria has found that many of the youth who were struggling with school and were reliant on extracurriculars or sports to get them into class had their lives thrown off-course due to the pandemic.

Racialized youth also often have to worry about having a safe space to simply exist, when they may have to be concerned about being targeted by police when congregating, she adds. “Every kid should have the opportunity to have something that they can afford that they are welcomed into. They deserve the opportunity to build a sense of identity.”

The heightened cost of living during the pandemic forced many to take multiple low-income jobs that offered no paid sick leave and had fewer options to self-isolate. A 2021 report by the Black Health Alliance, a non-profit that advocates for communities to increase health and wellness, shows that the northwest of Toronto, including Rexdale, Black Creek and York University Heights, had the highest rates of COVID-19 as of June 2021. Those neighbourhoods also have the highest proportion of Black people in the city.

The report also shows that systemic inequities and racism led to continued poor health-care availability and inequitable vaccine access. High transmission rates also hurt kids in those neighbourhoods the most, as schools faced more closures, there was lower funding for laptops and consistent internet access; learning loss as a result of these barriers continues to be a serious concern.

Funding was also highlighted as a consistent issue, with service workers stating in the report that instead of funding going toward shops and stores, it should have gone toward sustainable community programming. Other programs throughout the city, including one at the Scarborough Centre for Healthy Communities, offer free fitness classes for youth and also incorporate free meals and connections with social services. Emmonds points out that 13th Round has the capacity for more kids, which it hopes to accommodate. It just needs to get the word out. Meanwhile, the studio’s goals for 2023 go beyond boxing. In February, one of the young people at 13th Round offered to come in not to work out but to help prepare the meal for the group dinner. She likes to cook.

Emmonds can’t hide how happy that made her. “I tried to play it cool, but I’m very excited about it,” she says. The youth’s interest feeds into the studio’s long-term goals, whereby it can be open more often, with more staff to supervise, so that the teens can drop in when they want to.

“People will be grating cheese and putting out dishes...and it’s just a really organic family feeling. I think over time that it becomes more and more part of the program as we staff up.” For the group dinners, Emmonds will make a big pot of pasta, with the teens helping chop ingredients for the sauce. She is hoping some local grocery stores might be interested in sponsoring them so the meal service can grow.

“There’s a lot of love and affection that goes into the food, and making sure the environment is beautiful, lovely and clean,” she says. “So they know they are respected. It demonstrates our values: to celebrate that young person in every variation of themselves. We’re here for all of it.”

This mental health series is supported by the Joe Burke Fund for Social Justice Reporting, which was created in memory of Joe Burke, the late social justice advocate and lawyer.