MAD HOCKEY LOVE

FROM APRIL 2018 ISSUE OF WEST END PHOENIX

PHOTOS BY Jalani Morgan

The 2017/18 Maple Leafs possess the most gifted collection of young players in the club’s 100-plus-year history. Whether they can kick at the darkness and turn their promise into a long-awaited Stanley Cup is something only the spring gods can know

Suddenly, there appeared a blue car: duct-taped fenders and falling-off doors, yet painted entirely in Maple Leaf colours with a team crest on the side. It sat parked near the top of Havelock Street right around the time the Leafs faced Detroit in the first round of the 1993 playoffs, the home team having entered the post-season as underdogs, although that term is almost too comic-book-canine to describe a franchise whose fans have lived in the quicksand of disappointment since 1967.

Despite trading for the misunderstood working man’s superstar, Doug Gilmour, to play alongside Wendel Clark (one of them speared, the other slung fists, and they both scored a lot) the outcome was often the same – defeat – and the team wasn’t expected to do much. But a tiny Siberian, Tomsk’s Nikolai Konstantinovich Borschevsky, scored in overtime to surprise the Wings in Game 7 of round one. Anything was possible.

The next day, I sat with friends on the veranda of our Dovercourt Avenue apartment telling them about the car when, as if by magic, it drove past, a sideburned dude with a smoke in his mouth sitting behind the wheel, a hound riding upright in the passenger seat. We pointed wordlessly as they drifted past, a single parade float moving along an empty street lined only by us.

The Leafs faced St. Louis next – they beat them, too – and then moved on to play the Kings, led by Wayne Gretzky, who grew up cheering for Toronto. Inspired by a man and his dog, my friends and I headed down to the rink for Game 1 carrying guitars and wearing Canadian tartan blazers with beer cans stuffed in our pockets. We played for people pouring out of the Carlton subway until the Shuffle Demons showed up with a battery of horns (we ceded territory; they were professional buskers, after all). Fans wore colanders on their heads pretending to be Mike Foligno. Others had grown Fu Manchu moustaches like Wendel Clark, while some had used grease paint to draw whiskers on their faces in homage to the goalie, Felix “The Cat” Potvin. Some had Fu’s as well as whiskers – breaking all the rules – but that’s the way it was that spring and summer. The air was sweet, the sun was warm, and we marched in costume behind a weird blue car.

Toronto was in mad hockey love.

This story doesn’t have a happy ending: Few Leaf stories of the last 50-plus years do. Fans might remember Clark scoring a hat trick off the bench to tie Game 6, but they also recall how Gretzky suavely flipped the puck past The Cat in overtime. The next morning, I drove to Montreal for a gig at Club Soda while the Kings flew to Toronto, settling at the Westbury

to confect a plan to defeat the Leafs. Their plan ended up being simple: Let Wayne do it. “My greatest game as a pro,” Gretzky has said with the flat, measured tone of a killer, but it’s impossible for me to corroborate, having been called to the stage with the game tied 3-3 going into the third period. Our road manager had tried holding the house, but he couldn’t any longer, so we roared into our set propelled by nervous tension and anxiety about the game. I asked the crowd if anyone knew the score and a kid who’d been half-listening on a transistor radio raised his hand before coming on stage to do play-by-play of the last 40 seconds. Later on, I sat by myself and wept at the Main. I’d been cut by the cruel scythe of sporting fate, but whatever poured out was still blue. We stitched ourselves up and tried ignoring the jokes, the taunts, the barbs. Twenty-five years later, and with the playoffs just a few days away, I am ready to be opened up again.

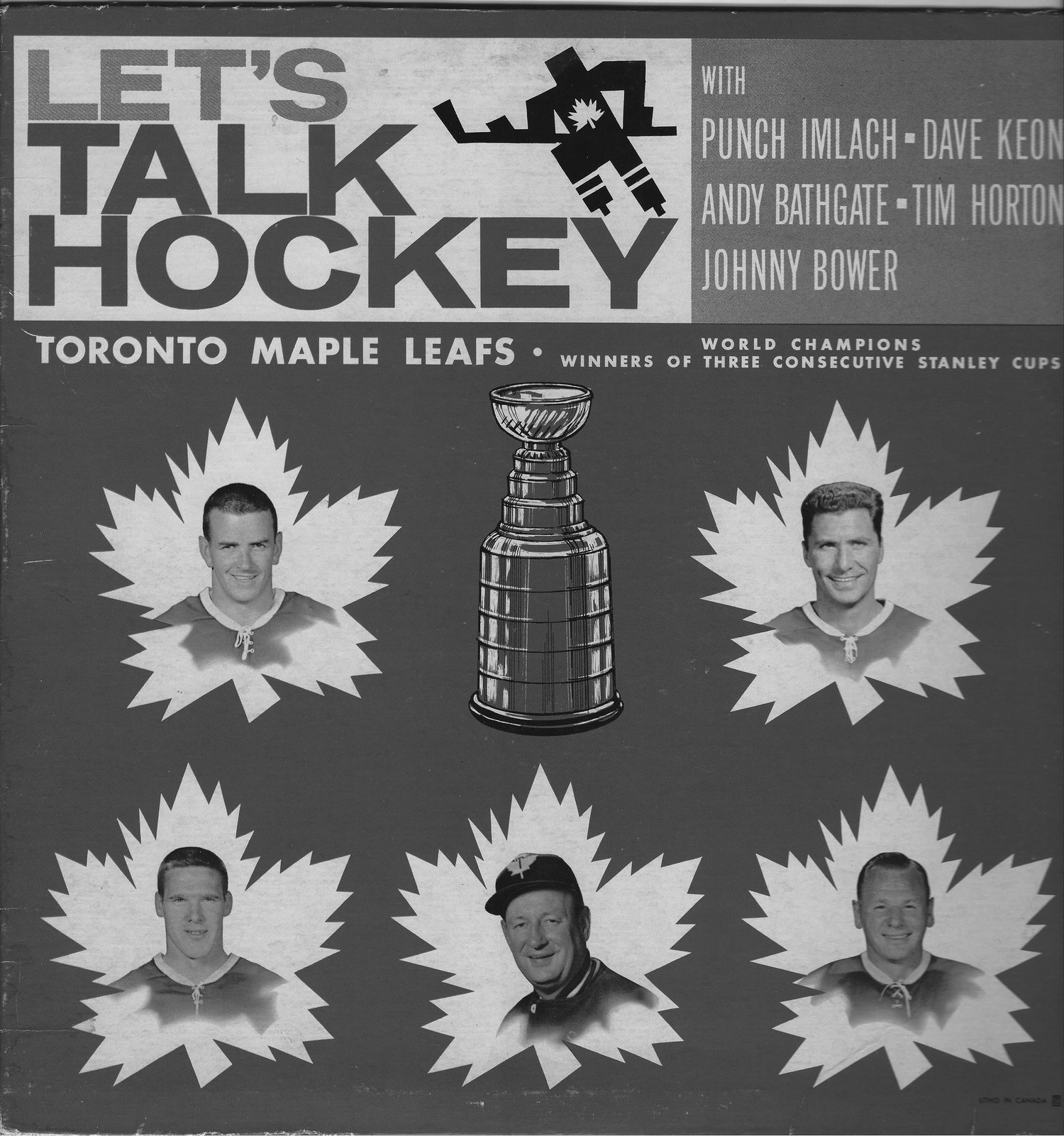

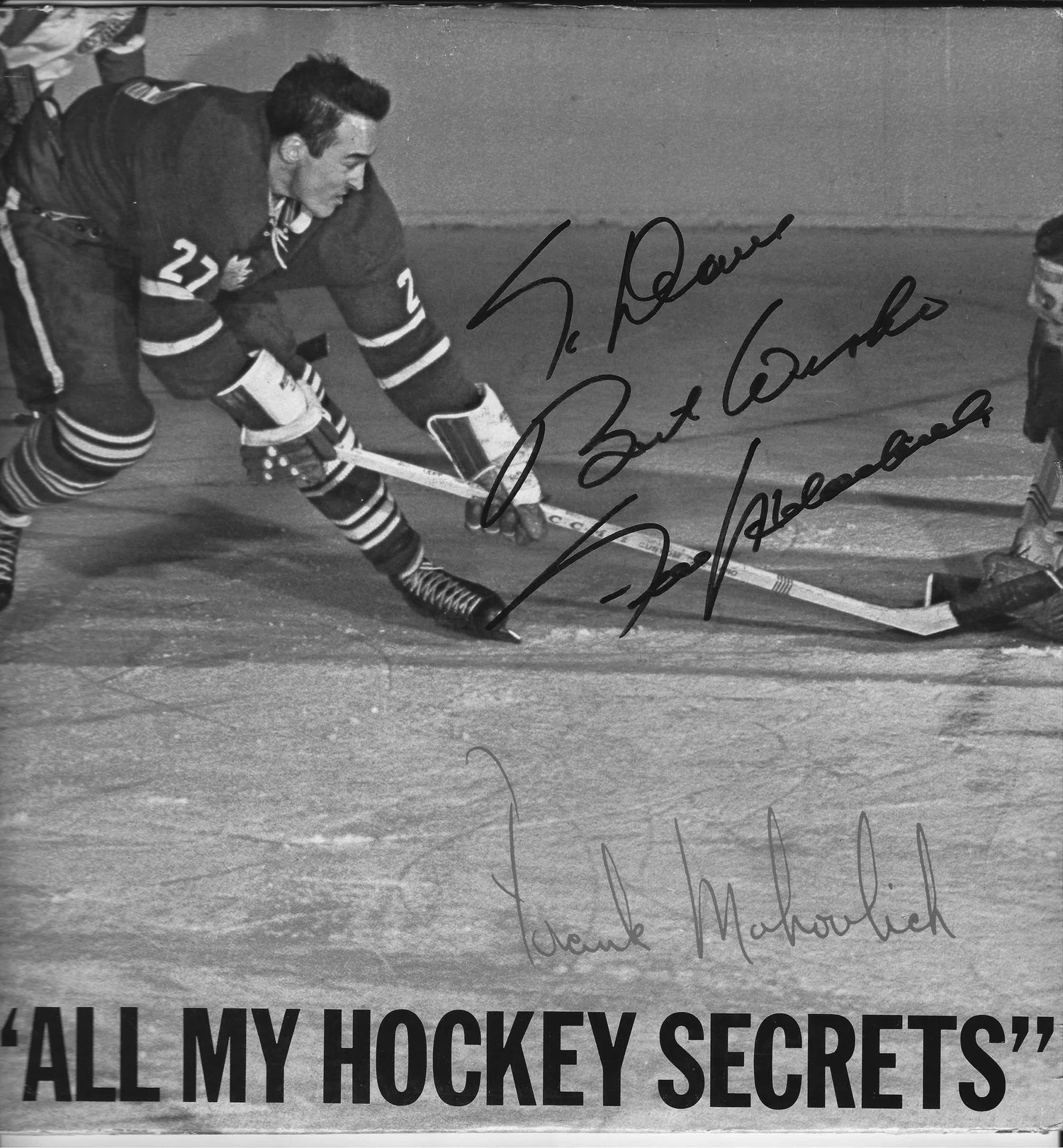

My journey with the Leafs started in the West End (without sounding too dramatic, it’ll probably end here, too). The first time I ever saw a professional athlete was at Cloverdale Mall, when my parents and I followed Johnny Bower, his hair slicked back and cool blazer swinging open as if he were moving to a Burt Bacharach melody. I have another early front-page memory of Mr. Bower – it’s what I would have called him had he not climbed into his car and drifted away – sitting with Leaf captain George Armstrong at the 1967 Stanley Cup parade riding in a convertible through a blizzard of confetti.

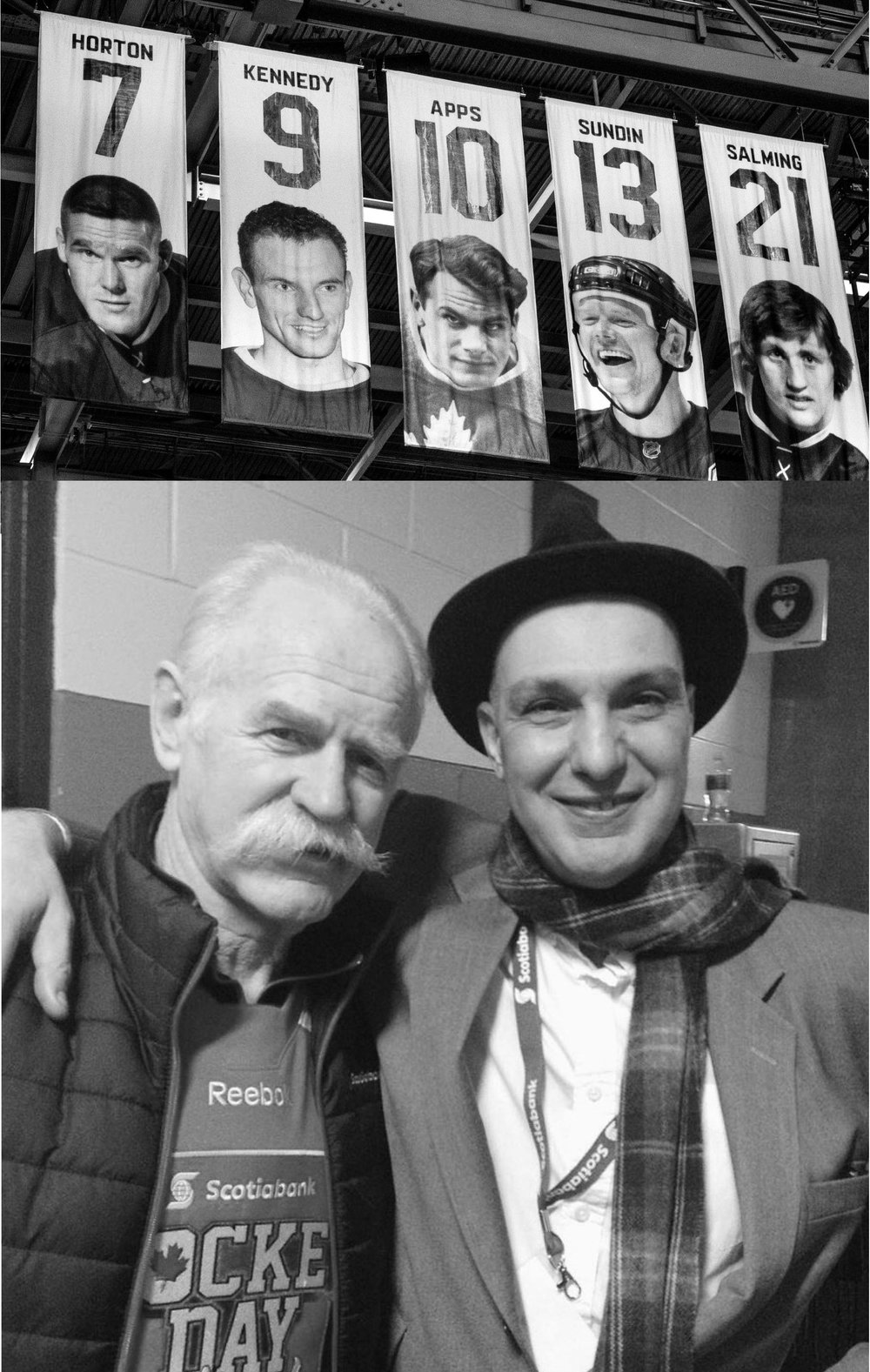

Other Leafs populated my youth: Paul Henderson signing my Esso Power Player album at the new Shoppers Drug Mart at the Westway Plaza on Kipling Avenue; Tiger Williams dining near us at Lee Garden on Spadina; and goaltender Turk Broda spending his last days at his daughter Rita Tushingham’s house, one street over from us in Etobicoke. There was also the bugle-nosed Eddie Shack cruising around the Pine Point Arena parking lot in his Pop Shoppe dune buggy and me and Billy Harris’s kids doing science projects together at Dixon Grove Middle School. Even though throwing support behind Montreal or Boston would have proven more rewarding, there was always the chance of running into a Maple Leaf at a bowling alley or coming out of a club, which Börje Salming did one night, leaving the Bamboo and peeling off a handful of twenties and dropping them in my guitar case.

Fans were rewarded for following the Leafs in the 1970s – hard-fought seasons, and players with aplomb and wonderful hair, among them Lanny McDonald and his feather duster, Errol Thompson with his steel-wool perm. But no one knew how good we had it until everything fell apart, starting with the venal owner, Harold Ballard, and ending with entitled fans sitting in $400 seats throwing $300 sweaters on the ice. Not counting the flirtations of ’93 and some good Mats Sundin teams in the middle 2000s, the Leafs were a bladed punchline. You didn’t have to be a sports fan to acknowledge their aching futility. They were the worst team in the history of sports who played at the epicentre of their game, a fact made even more frustrating after the city grew out of its uncertain teenagehood into a forward-minded young adult. The blue car disappeared and players nearly vanished. I ran into Mike Walton at McCormick Arena, where he watched the skaters and cried.

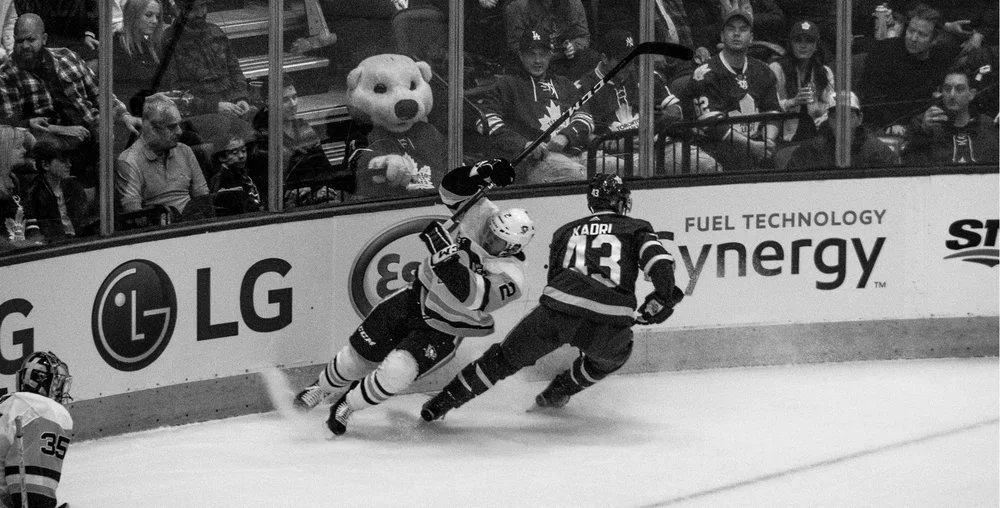

A few years ago, the organization was handed over to Mimico’s Brendan Shanahan – in this instance, I prayed for West End karma – and something unusual happened: good luck. The Leafs won the league’s draft lottery – they won it by finishing last – and drafted centre Auston Matthews, a desert kid who scored four goals in his first game and was named the league’s rookie of the year, forcing every basement expert to see that, after decades in the wilderness, all the team needed was a desert kid who scored four goals in his first game.

Matthews has been everything to Leaf fans – an instant superstar and one of the league’s most gifted talents. He skates with a knightly stride and thinks creatively, sometimes tipping the puck on its end to shoot. He stickhandles as if he were a vendor hustling three-card monte – the puck here, then there, then not there, then in the net – and his heart rate is that of a person vacuuming the hallway, at least until he scores, at which point he’s all of his 20 years: windmilling his arms and hollering joyfully at William Nylander, the young Swedish magician who lines up to his right.

There are others; even others from the West End. Etobicoke winger Connor Brown possesses a resolute sharkness – back hunched and moving with stealth across the ice – while Mitch Marner, for years a fixture in the city’s minor hockey system, is the kid every kid dreams of watching play; partly because he seems as if he’d been down with his toy trucks only a moment before, and partly because he never cheats a play in favour of the straight line, honeycombing about the ice in a way that suggests that hockey might actually be fun. There have been a few James at 16 jokes made at Marner’s expense – during an overtime game last year, his teammates asked if he was excited to be staying up past his bedtime – and sometimes Marner overcompensates for his boyishness by celebrating with over-the-top manly exhortations. The Leafs are young: They weren’t around for Johnny Bower, but they weren’t around for five decades of losing either. They are guileless and ignorant of most failure and Auston Matthews wouldn’t know Derek King – a famously wrong-headed Leaf signing – from Burger King.

This week, the Leafs will enter the playoffs with as good a chance of winning the Stanley Cup as any team in the tournament. Their renewal as an NHL power comes after a sledgehammer winter and, if it wasn’t Donald Trump one day, it was Doug Ford the next. Raptor DeMar DeRozan told everyone he was battling depression and Blue Jay Roberto Osuna was so down he couldn’t even hold a baseball, let alone throw one. In this climate, the Leafs became very good, and with the world a mess, we might spare a few moments to get swept away by a hockey game this week, as the post-season starts in a handful of cities, including ours.

Sport can be nothing but a panacea and sport can represent the most narrow-minded aspects of who we are and sport can be the playground of the rich and famous and sport can refuse to give Colin Kaepernick a job. But sport can also kick at the darkness till it bleeds daylight. It can infect a city and its neighbourhoods with joy and drama and it can remind us about the vibrancy of life, and if you’re lucky, it will produce a blue car driven by a dude and a dog. It’s these things we’ll remember most when we talk about the spring of ’18.