CULT FOLLOWING

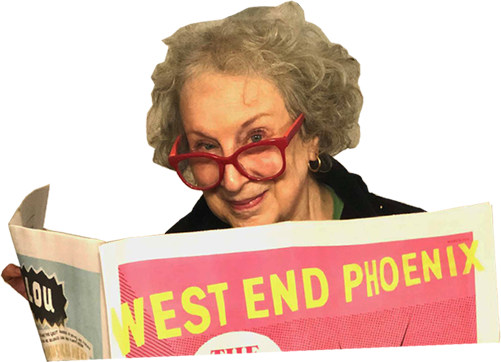

Margaret Atwood: Four books examine the spells spun by charismatic leaders

In view of the storming of the U.S. Capitol, I’ve got cults on the brain. Some people are now claiming to have had the best of intentions: It was in the interests of democracy that a violent mob was threatening to murder the elected representatives of that democracy, they say. By what hypnotic magic is a group hoping to save (fill in the blank) transformed into a cynical cult, run for the enrichment of a con-artist cult leader? Synanon, for instance, began as a genuine kick-addiction outfit, but ended as a failed version of Murder, Inc. In that case, power corrupted.

Unfortunately, we’re all vulnerable to appeals to our better natures. You don’t want babies to have their blood drunk in the cellars of pizza parlours, do you? Of course you don’t! Donate here! But how do we tell the sincere reformers from the phoney ones preying on the fearful and the gullible? It’s not always easy. (Hint: Check to see if there really is a cellar in the pizza parlour.)

Sometimes cults end in mass suicides; sometimes in the flight of the leader plus all the money; sometimes in jail sentences. And sometimes they just carry on, because once you’ve been brainwashed it’s hard to get un-brainwashed. Losing your personhood to the hive mind of the Borg has its appeal: You’re doing the will of your godlike leader or ideology, all in the service of the Greater Good.

Here is a clutch of books that address these experiences.

Talking to Strangers: A Memoir of My Escape from a Cult by Marianne Boucher

The first is a graphic novel: Talking to Strangers: A Memoir of My Escape from a Cult, by Marianne Boucher. In the ’90s, an 18-year-old gets picked up on a beach by a pair of recruiters from the Unification Church. These people claim to understand her and accept her for who she is. Remarkably quickly she’s become a starved, sleep-deprived zombie, separated from her family – now framed as evil – and scrounging money on the streets, believing she’s helping starving children. Her parents hire a deprogrammer who’s been through the cult already, and… but I won’t spoil the plot. It’s a gripper, especially if you have teenage kids. Or have been one, come to think of it.

The Last Good Man by Thomas McMullan

Next up is a novel: The Last Good Man, by Thomas McMullan. Civilization has gone pear-shaped in the cities of England, and our fleeing hero searches out his cousin, a top-ranker in a village that’s organized itself around the blame-and-shame principles of what feels either like 17th-century Puritanism or a physical manifestation of Twitter-mobbery. There’s a Wall, and accusations are written up on it anonymously, as in the first phases of the Cultural Revolution. You don’t get a trial: To be accused by enough people is to be guilty. Punishments vary, but all are painful and all are for your own good. There’s a charismatic founder, there are enforcers. What can go wrong? Quite a lot, as it turns out. Is this our future, Dear Reader?

Brothers by Yu Hua

Next is Brothers, a novel by Yu Hua, and a runaway bestseller in China. The rampaging Cultural Revolution and the subsequent materialist reaction against it are treated largely as farce, through the lives of two men who are sworn “brothers.” At a distance of 40 or 50 years, it now appears safe to remember those who were destroyed by the Red Guard, a cynical cult if there ever was one. The grandchild generation is old enough to write novels, and has been doing so with a vengeance. This one takes a rowdy, angry, no-holds-barred approach. No one is left untainted, and there are no get-out-of-jail-free cards.

The World Turned Upside Down: A History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution by Yang Jisheng

Finally, a history book: The World Turned Upside Down: A History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, by Yang Jisheng. Here it is, laid out on a plate: Mao’s motives (fear of an uprising against him, like the anti-Stalinism that was happening in the USSR in the late ’60s); his building of his own cult of personality; the central players; the power struggles; the incitement of young mobs to inflict terror on specific groups in the name of saving the Revolution; and finally, once the cult leader was dead, the downfall of the Gang of Four, engineered in the utmost secrecy by a group that knew they had to topple before they themselves were toppled.

What do all cynical cults have in common? Nothing, ideologically. It’s not a matter of Left versus Right, or – to dial back a few centuries – of Cavaliers versus Roundheads. Any ism is capable of atrocities, and not all isms are run for profit by greedy megalomaniacs. But mandated sadism is certainly one of the touchstones of a cynical cult: struggle sessions in which you’re beaten to death with belt buckles by the self-righteous, egging one another on to demonstrate how pure they are.

How do you tell a con game from a just cause? Sometimes it’s a fine line. But when you peel the onion only to discover there’s no centre except for the self-interest of the leaders, you realize you’ve been had. The cruellest act of a phoney utopian scheme is the betrayal of its followers’ hopefulness and idealism. As Marianne Boucher’s deprogrammer explains to her, she thinks she’s been working selflessly to buy cans of tuna for starving children. But there are no cans of tuna.